To Dr. Irons’ surprise, Walter Noel’s blood smear contained something other than malaria parasites; it contained oddly shaped sickled red blood cells. What the young Dr. Irons had stumbled upon, and apparently what had never been described in the annals of medicine, was the first microscopic evidence of a new disease: sickle cell anemia. Apparently, Walter Noel, a black male dental student from Grenada had sickle cell anemia, and whether he also had malaria was never substantiated, likely suspected, but definitely applicable. Was it happenstance or were these two diseases – malaria and sickle cell anemia – somehow inextricably connected through history?

Malaria is an infection by a single-celled parasite and its transmission to humans involves a vector, the mosquito, so the transmission occurs in a rather odd fashion. To be sure, when we think of infection, like the Flu or the Common Cold, we think of such maladies as being transmitted from person-to-person – aerosolized viral particles from a sneeze – and more times than not, most infections are transmitted person-to-person. But that is not always true and certainly not true with malaria; rather, an intermediary, a vector, transmits malaria and in this instance, it is the mosquito. The female Anophelesmosquito must first dine on a malaria-infected person, sucking-up in a vampire-esque fashion malaria-contaminated blood, and then in short order that same female mosquito alights upon an uninfected and unsuspecting customer for a second meal where upon she injects her malaria-infected saliva into the bloodstream transmitting the infection to the next person.

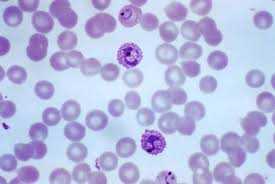

Once in the body, malaria parasites don’t just swim around in the bloodstream, they actually take up residence inside the sanctum of red blood cells, and by doing so, the parasite is protected from the immune system’s white blood cells, those cells tasked with beating back foreign invaders. This is a crucial step in the malaria life cycle; the same step the HIV virus takes, crawling insidiously into a blood cell, hidden from immune system surveillance. Image left shows a bunch of red blood cells but a few darker staining cells are the malaria-impregnated red blood cells. Once inside the red blood cells, the malaria parasite is then free to reproduce daughter parasites unhindered by such things as Killer T-cells of the immune system. Eventually the malaria outgrows its cellular home forcing the red blood cell to burst, termed cell lysis, spilling all those daughter malaria parasites into the blood, many of whom get killed by the Killer T-cells, but many more still who make their way into yet other red blood cells, breaching cellular integrity, and repeating the life cycle all over again. The constant cell lysis – red blood cells bursting – is what produces the chronic malaria anemia; between the anemia and the infection giving rise to fever, muscle aches and pains, and chronic malaise, people infected with malaria don’t feel all that well, not very well at all.

You might think that malaria should lead to death; it doesn’t in most cases, at least not for many years. This is the story of most parasitic infections and it is an important story to understand; parasites don’t usually kill their host unless killing the host is part of their life cycle. Simply stated, it would be decidedly disadvantageous for a parasite like malaria to kill its host, because by killing its host it kills itself and all its daughters. In death of the host, the parasite has no way to transmit itself – if the host dies the parasite dies with it – which is why most parasitic infestations are chronic rather than lethal.

…stay tuned…the story will continue…

John Bershof, MD

John Bershof, MD is a plastic surgeon who has been in private practice for over 25 years. He is the author of numerous medical articles as well as the first textbook of medicine for mobile phones, entitled skynetMD 2005-2015. An essay entitled Gin & Tonics, Clerics, and Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?, which was extracted from one of his future as yet published books was featured in The Antioch Review.

While working on the medical textbook skynetMD for mobile phones, Dr. Bershof, perhaps not too surprisingly became more interested in the backstories of medical history, like who was Lou Gehrig, what is Lou Gehrig's disease, what was his lifetime batting average for the New York Yankees—.340, nineteenth overall—and who invented baseball anyway. Questions such as these piqued Bershof's interest. Having read At Home 2010 by Bill Bryson, his engrossing narrative journeys room-by-room through his Victorian English countryside home, a former rectory, where each room is a chapter about domesticity, about home. It occurred to Dr. Bershof that in similar vein he could take the reader disease-by-disease as jumping off points into human history, science, medicine—his canvas blank, no subject not within reach—and learn a little medicine along the journey.

The ability of a book that is heavily fortified with science and history to connect with a general readership can be challenging; Dr. Bershof through storytelling, humor, jumping off points and personal anecdotes, accomplishes it, written in a language fleeced of the jargon that normally accompanies such narratives. The first two books, The First History of Man published in 2020 and The Second History of Man published in 2021 are available in print, ebook and audio. The Third History of Man is in final stages of editing to be published in 2022, with more volumes to come after that.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.