This blog “Gin & Tonics, Clerics and Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?” is a blog series over several months that covers:

• Malaria

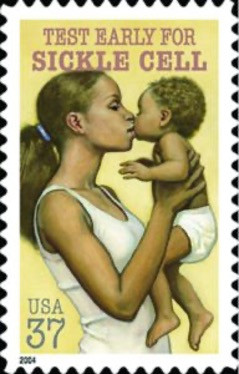

• Sickle Cell Anemia

• Invention of the microscope

• Origin of Afternoon Tea & Crumpets

• Origin of Gin & Tonics

• The Parson Scientist

• Darwinian evolution

• Parasite infections

• Age of Discovery and Imperialism

• Boston Tea Party

• Morton Stanley and Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?

Grenada is a beautiful island country at the southern end of the Grenadines, an archipelago in the south Caribbean Sea. The Grenadines include popular beach resort destinations like Petit Nevis, St. Vincent, Martinique and Grenada. To the south of Grenada are the islands of Trinidad & Tobago and a bit further south is the northern coast of Venezuela. Grenada was a French colony from 1649 through 1763, then a British colony until 1974, when the Grenadians won their independence.

Walter Clement Noel, born in 1884 was a 20 year-old black male from Grenada studying dentistry in Chicago. In 1904, Noel took ill and was admitted to Chicago Presbyterian Hospital, suffering from respiratory symptoms and general malaise. Medical intern Dr. Ernest Irons performed the initial medical work-up on Walter Noel and presented his findings to his Attending Physician Dr. James Herrick. Both Dr. Herrick and the young Dr. Irons felt Walter Noel had malaria. A person from a near equatorial Caribbean island such as Grenada presenting in the United States with malaria was not terribly unusual, but what happened next was.

As part of the evaluation, Dr. Irons performed a microscopic peripheral blood smear exam on Noel’s blood, expecting to see tiny malaria parasites. In the early 1900s microscopic examination of a blood smear was relatively new in medical practice, it was like the “in thing” for a doctor to know how to use a microscope. Although Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel is credited with having fashioned the first microscope in 1620, it was fifty years later in the 1670s when another Dutchman Antonie van Leeuwenhoek – those Dutch loved grinding glass into lenses – thought to use the microscope in order to peer into the world of invisible life. Van Leeuwenhoek used his dimly lit microscope, lit by reflected candlelight no doubt, to describe the microcosm world of bacteria, red blood cells and for reasons that escape history, male sperm.

Yet despite van Leeuwenhoek’s seminal work – double entendre notwithstanding – having created the field of microbiology, it took another 200 years, towards the end of the 1800s, for the medical world to catch on and utilize the microscope as part ‘n parcel in medical diagnosis and treatment. After all, microscopes were not that easy to come by, difficult to make and cost more than a pretty coin.

Another reason of course for the delay in understanding the spread of infectious diseases, other than the nascent field of microscopy, was that overpowering one thousand year incorrecttheory of Galen of Pergamon, the 3rdCentury Greek physician within the Holy Roman Empire who decreed that infection was spread by miasma, by bad air. No one, not for a millennium, not even the Pope would dare question Galen. Galen was brilliant and often insightful; but his dogmatic medical theories, even the wrong ones, persisted through the Dark Ages, through the Medieval Ages, needing the Renaissance to bring many of Galen’s false pillars down. It wasn’t until the end of the 19thCentury, between the germ theory experiments of the Frenchman Louis Pasteur in 1860 who proved conclusively that bacteria caused the spread of infection – his non-pasteurized milk theory comes to mind – coupled with the German Robert Koch’s 1884 postulates of infection spread, that the fledgling field of microbiology and infectious disease was off and running.

…stay tuned…to be continued…

John Bershof, MD

John Bershof, MD is a plastic surgeon who has been in private practice for over 25 years. He is the author of numerous medical articles as well as the first textbook of medicine for mobile phones, entitled skynetMD 2005-2015. An essay entitled Gin & Tonics, Clerics, and Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?, which was extracted from one of his future as yet published books was featured in The Antioch Review.

While working on the medical textbook skynetMD for mobile phones, Dr. Bershof, perhaps not too surprisingly became more interested in the backstories of medical history, like who was Lou Gehrig, what is Lou Gehrig's disease, what was his lifetime batting average for the New York Yankees—.340, nineteenth overall—and who invented baseball anyway. Questions such as these piqued Bershof's interest. Having read At Home 2010 by Bill Bryson, his engrossing narrative journeys room-by-room through his Victorian English countryside home, a former rectory, where each room is a chapter about domesticity, about home. It occurred to Dr. Bershof that in similar vein he could take the reader disease-by-disease as jumping off points into human history, science, medicine—his canvas blank, no subject not within reach—and learn a little medicine along the journey.

The ability of a book that is heavily fortified with science and history to connect with a general readership can be challenging; Dr. Bershof through storytelling, humor, jumping off points and personal anecdotes, accomplishes it, written in a language fleeced of the jargon that normally accompanies such narratives. The first two books, The First History of Man published in 2020 and The Second History of Man published in 2021 are available in print, ebook and audio. The Third History of Man is in final stages of editing to be published in 2022, with more volumes to come after that.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.